A Tale in Whitewater Safety

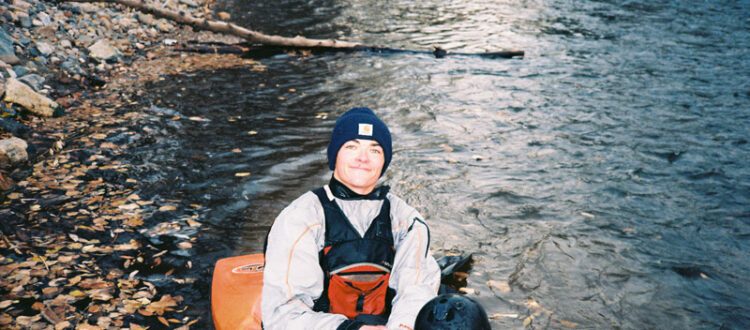

By Nathan Dicker, Team Watershed 2021

I’ve always believed whitewater is a sport to push limits, that’s why I love it. It gives me the same thrill of going beyond my boundaries that rock climbing and snow sports do. Clearly, these sports are not inherently safe, and that’s barring an even more immense risk in backcountry snow. Even so, the river can be an equally treacherous environment. I will say that while pushing my limits, there have been times where I may have toed the line of what is justifiable. But in doing so, I’ve learned valuable lessons.

I’ve been on the river for nearly 14 years now, and if there’s one thing I’ve noticed about myself it’s that I tend to take the exciting route. Running rapids backwards, spinning, flipping upside down, you name it. The majority of my time on the river has been spent on Class III/IV sections, with a handful of IV+/V thrown in. The longer trips I’ve been on always had an immense amount of flat-water, allowing me to take it all in. With my time spent on the river, as well as a couple of summers of junior guide camp and ARTA Rowing School, I was able to gain a better understanding of river running and river safety. I also developed a profound respect and fear for the power of whitewater.

In July 2012, I was on a river trip with a fatality

While the river can be incredibly dangerous, deaths from rafting accidents are still uncommon unless reckless behavior is involved. But accidents happen, and in the summer of 2021 my crew and I suffered a freak series of events that caused things to go terribly wrong. That trip had a deep impact on me, in both negative and positive ways. I got back on the river after taking a summer off — my love for it was just too strong to keep me away. Nevertheless, I still have anxiety every time I get on the water.

Let’s talk about whitewater safety

I will say, as mentally difficult as that experience was for me, it taught me one important lesson: the utmost importance of safety and knowledge on the water. I don’t want to scare anyone away from the river by discussing this experience, but what’s more important is understanding why responsibility and competence cannot be substituted. Even though this tragedy was not due to reckless behavior, accidents can happen on the river. With that said, I’ll say this: wear your personal flotation device (PFD), scout your rapids, plan your line, make good decisions, and know your s***.

Now, despite my experiences showing me the dangers of the water, I can’t really preach the “I’ve never done something wrong, don’t be stupid…” line. I don’t believe in dishonesty but I do believe in learning from mistakes – sometimes other peoples’ too, so here is one of mine.

My story begins

This past summer, I finally got a hardshell kayak. I previously had two or three days in a hard kayak under my belt and had learned the basics of a roll and maneuverability, but that’s about it. So, I spent the first couple weeks in my pool dialing in my roll, and in August moved out to Fort Collins (FOCO) for my sophomore year of school. For those who don’t know, the Poudre Canyon opens up about 10-15 minutes from Colorado State University (CSU), so when I got to FOCO I had more access to whitewater than ever before. You can only imagine what that means for someone with my level of stoke.

I was up there scouting lines, running ripples, trying to learn to surf and pick up other activities almost every day. Being incredibly careful, I was scouting routes carefully and only running ones I was comfortable with. Soon enough I got the hang of my boat, quicker than expected.

Eventually, the day came that I was up at “the beach” – a local sport climbing crag – with some friends. I had them drop me about 150 yards upstream to paddle down the river to the area where they were climbing. It was nothing big, just some class I/II ripples, some shallow technical whitewater. I planned on belaying my friends and then heading down to paddle some bigger whitewater below.

Prepping for takeoff

From the road, the water looked like it could be class III or more, but after getting a little antsy after belaying, I walked down to scout closer. I realized it was much more serious than I had anticipated. The rapid started off with a little drop and some more ripples, and it dropped harder than I’d ever seen, with a rock jutting out a foot or two under the water on river left (creating a break in the waterfall-esque feature). What followed was a decent-sized drop with another rock jutting out the center of it, and a crescent undercut on river right that one would have to redirect with prodigious precision to avoid major mishap. It’s safe to say my class III kayaking was well below the level of this section – but, having a good deal of experience reading whitewater, I decided to keep thinking.

Having walked and scouted the whole rapid four or five times, I knew a few things. One was that I had the skills to get through all but about 10-feet of this rowdy rapid. The intro was easy, the buildup to the big drop wasn’t much, the exit was chill and the drop was wide, flat, and not that high angled of a tongue. Second, I knew the risk was high for me messing up the line, but low for me having a serious issue. I knew the chances of equipment damage or loss were moderate, and chances of bruises and bumps were high, but the chance of serious injury or death wasn’t. The only severe danger seemed to be one rock, but I would be protected by an eddy and some shallower flat-water.

So, I hiked back up, handed my friend my throw bag and camera and told them to keep recording unless something goes incredibly wrong. I got in my boat, double-checked my gear, hit the pre-run-good-luck-roll, made a “rock on” with my hand and paddled into the current. The first run on this rapid was as brutal as it was beautiful. I went from a couple of months of experience in a class III boat to tackling this seemingly class V rapid – needless to say I felt the stoke of a lifetime.

I ran up the side of the river to see the footage, only to find out my friend messed up with the record button. Devastating. Either way, my stoke was even higher than ever and I took this as a reason to run it again – “no footy, no send” they say. Since I just ran it I felt I had the whole route covered, so I got back in the boat and pulled out of the eddy, full of adrenaline.

Round 2

This is where I start to learn my lesson. I was tired, my brain wasn’t as sharp due to the adrenaline, and I veered too far right. I didn’t stay left and go straight like I did before, but instead went right and had to quickly redirect at the rock splitting the current. This isn’t how I planned to take this on.

After the big drop, I sank a bit into the aerated water due to my lower-volume boat and was so tired I wasn’t able to paddle effectively through this section. I bumped the rock on the left side of my boat and put my hand out to brace. Luckily I got around the rock no problem and stayed upright. However, with only one hand on my paddle I was unable to pass through the eddy behind the rock, causing the line to flip me.

The problem was the momentum this sent me off with. The awkward currents I had been in sent me left to the shallow rocky end where I smacked my head. I was disoriented for a second but came-to shortly after. The hit screwed my chance of rolling, and it was here where I learned my first two lesson: 1) Even if the consequences are low (flow-wise), there are always rocks and they hurt. 2) Boats are heavy when they fill with water, so buy some dang float bags.

That wasn’t the end of my learning experience, however.

Third time’s the charm

I went back up to the river a week or so later to try some of the newly established climbs in the area. My plan was to try the same rapid, do it well, take photos and perhaps do some climbing. Unfortunately, this third run went even worse than the second.

On this third run, I overcompensated in the worst way. Remember that rock on river left under the big drop? I ended up tumbling over it, being thrown left. I tried to stay left to avoid the eddy behind the rock in the middle of the second drop. Turns out I didn’t have time to worry about that, considering I was halfway flipped over by the time I was down the larger drop. Upside down, I was shoved around by weird currents, staggered by rocks and the final drop of this section. Safe to say, this time I was terrified.

I should have rolled once back in flat water, but after being thrown around so much it didn’t even occur to me. I immediately pulled my skirt and swam. Unlike the second run I wasn’t able to pull my boat to the side, and in an attempt to keep my boat above water, I was pulled into the current and down the rocky shallow section below. At this point I lost my paddle and was clinging to my boat, only to be sent into a rock jutting out of the current, causing a bone contusion on my leg and bruises all around. After bouncing and bashing off the rocks and being dragged down the river, I was able to pull my boat to the side of some flat-water.

I was bruised, exhausted and deeply shaken.

Ego Check

It’s safe to say, my journey down this section of rapids was quite the humbling experience. My lost paddle was luckily found a few weeks later because my name was on it (another lesson)! Frankly, I thought I had broken something during the swim, though it turns out it was just some contusions and aching. The real damage was the vicious hits to my ego. While I have experience in inflatables, it was all of a sudden incredibly clear my hardshell skills were subpar, which was a naïve thing to disregard.

Lessons I learned

The fact this turned out to be a class V+ section drove that thought home even harder. What I’d consider the most important lesson was even though I had people around when I did this, none of them had swiftwater rescue experience. In truth, none of them had been on the river before. This was beyond foolish and quite possibly the greatest mistake I have made in my 13-years on the river, and 20 being alive. We were an hour out from any cell service, meaning any help or rescue may have been too late if things really went south. Looking back, I should have known that just because I thought the likelihood of an accident is low, it’s never completely out of the picture.

Quite possibly the greatest and most important lesson I have learned in whitewater is to never boat alone. It is reckless, stupid, and just because you’re the only out there doesn’t mean you aren’t the only person who can get hurt.

Out of all the safety no-no’s ingrained into my experience, for some reason, boating alone did not click that day. I knew it was a risk, but until that day, I didn’t fully process that one should, under no circumstances, boat without others that have at least some form of relevant training. I needed a safety set, other class V boaters, and frankly, someone with greater experience than I with me.

Reflection

Again, I would like to reiterate this point, never make this mistake, and never again will I. I’m simply grateful that I’m able to sit here and tell you this story today.

I feel that I’ve had an immense amount of personal growth in the past five months. Besides understanding and learning from my mistakes (not only with whitewater), I have come to better realize some of the impacts my actions can have. I have been more introspective during this semester about my studies, career, sports, as well as just way of life. I am not big on egos. I tend to be more self deprecating. But in my river experience, where my ego mattered, it was absent, and where it needed to be absent, it showed.

Egos really have no place on the river. Sure, you should know your skills and be confident, but situations can hit the fan if you overestimate yourself or get incompetent. That can be avoided by knowing one’s true limits. But one lesson I have learned outside the river is that while self deprecation is not bad, it should not be constant.

A good friend of mine has been preaching this recently: know your strengths, know what makes you a good person, and don’t be afraid to say it, especially to yourself. I know I have a lot to learn, but I also know I work hard, care, and have skills that make me, me. One thing I know for sure? Put me in a boat and I’ll send it. I still have much to learn about hard shells.

And that, that is the story of Nathan Dicker and Supercollider.

Nathan: 1

Supercollider: 2

Stay tuned for next season.